Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

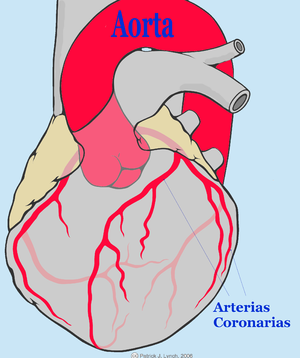

| The coronary arteries and the aorta, which carries blood to the rest of the body. |

I've just spent four more days in the ugliest, most ill-fitting clothing known to man -- the hospital gown.

When I looked at my naked body -- shaved, bloodied and bruised -- in the mirror of my hospital bathroom Tuesday afternoon, I winced. But soon, I had my first hot shower and first shave since open-heart surgery on Friday, and I was going home.

I survived not only the operation, but food and sleep deprivation. The medications I received altered my taste buds, a problem that continues.

Food tastes funny

Even familiar salt-free almonds I roast at home tasted weird. The hospital's orange juice from concentrate tasted so sour I thought it was grapefruit, which is incompatible with my cholesterol medication.

Because of a heart murmur, I needed a new valve fashioned from a cow's heart, but I required no bypasses. My surgeon said my 66-year-old coronary arteries are whistle clean, affirming my no-meat diet, which is heavy on heart-healthy fish.

I have no memory of the operation, the sawing open of my breast bone and the replacement of a calcified aortic valve that was barely opening. Before I went in, the operation was estimated at four to six hours, from putting me to sleep to waking me up in the recovery room.

Recovery is real challenge

One moment, it seemed, I was talking to a doctor and male nurse as they administered anesthesia Friday morning at Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, and the next moment I awoke in the Cardiac Recovery Unit -- on a bed with my hands restrained so I couldn't try to remove a breathing tube jammed down my throat.

I also had chest drains, catheters in arteries in my throat and arm; a temporary, portable pacemaker with two hair-thin wires into my heart, EKG posts and leads all over the place, and an IV drip of saline solution.

I couldn't see the line of stitches obscured by dried blood that ran vertically down my chest -- about 9 inches long -- covering where my femur had been opened for the operation, then secured with stainless-steel ties. Under that were horizontal cuts for pacemaker wires.

And my chest hurt like hell. Five days after the operation, I still feel both a heaviness and a tenderness. I was warned about raising my hands above my head or bending down to pick up something.

No solids for two days

I had stopped eating about 10 Thursday night, when I had some red grapes while watching TV. My first solid food in the recovery unit were diet lemon ices early Saturday, followed by a scrambled egg, large tater tots, a slice of toast and decaf coffee on Sunday morning.

Doctors placed me on a meatless diabetic's diet -- no salt, no sugar, no caffeine, no taste -- even though I'm not diabetic.

I was dying to get out of the recovery unit, though had nothing to look forward to in terms of food. When the physical therapists came by, I impressed them with my ability to get off the bed and walk normally -- thanks to a solid year of going to the gym five days a week and losing 30 pounds.

The man who came to transport me on my back to the 7th-floor Cardiac Step-Down Unit said I was the first recovery unit patient he had seen who was able to walk on his own.

Best food isn't shared

Six more meals brought to my private room would follow before I was released Tuesday afternoon, and I actually thought a couple of them were palatable.

One was Monday's lunch of pale, farmed salmon that had been cooked through but still retained some moistness, served with scrumptious oven-roasted potatoes, and Tuesday's lunch of seasoned, baked fish with mashed potatoes and melted Smart Balance spread.

When I asked for fresh vegetables -- asparagus, carrots, broccoli -- they invariably were cooked too much. A fresh fruit cup on Tuesday held two kinds of sweet melon.

Sleep was nearly impossible. My vital signs were monitored frequently, sometimes on the hour, and to measure blood sugar, the end of one of my fingers was pricked by a needle -- and a brown scab formed.

The door to my room was left open, flooding part of it with bright light. Telephones rang, patient call chimes echoed and monitors beeped.

I could hear conversations in English, Tagalog, Spanish and Caribbean patois.

One form of all-night torture were sleeves slipped over my lower legs that inflated every minute to fight blood clots.

Electrocardiograms were taken first thing in the morning, once at 5:15 a.m. by a woman who could be someone's Italian grandmother. While she hooked me up to the machine, I silently admired her ornate, gold eyeglass frames.

The best food at the hospital is brought in by employees for "lunch," which could come at 2 a.m. at this 24/7 operation. One of my night nurses was a gap-toothed Asian Indian who had just eaten her home-cooked meal of rice with spicy fish.

Boy, I would have loved some of that.

Good and bad shifts

I asked an elderly woman whose English had a Caribbean lilt why she was working in the middle of the night.

"I want to eat bread," she said, but added she slept poorly, because there is nothing like "night sleep."

Marta, the Polish nurse who took care of me during the day, said she worked a 36-hour week -- three days of 12-hour shifts. I heard her on the phone one day, expressing concern that an upcoming shift would have only three nurses for 21 patients.

When you ask doctors or other employees why the food served to patients is so bad, they invariably say, "It's a hospital" or "It's a big institution."

Other patients

I walked around the Cardiac Step-Down and Cardiac Telemetry Units and chatted with other patients.

A Cuban man said he lives in Miami and had worked for 30 years, most of the time in a factory producing milk and eggs, and never had to learn more than a few words of English.

We spoke in Spanish and he laughed heartily when I said the food is "como mierda."

A man in his Seventies was recovering from an operation to remove a tumor from one of his kidneys. He had two bypass operations in the past. As he was trying to peel a banana, I noticed he had no fingers on his right hand.

A woman in her Sixties had taken advantage of a 2-for-1 sale, getting a new heart valve and a triple bypass at the same time. She thought her valve came from a horse.

Rich ethnic stew

During my four days in the hospital for the operation and two and a half days for tests the week before, I met about one hundred employees, from Dr. Adam G. Arnofsky, my cardiac surgeon, to a Dominican woman who was mopping floors Tuesday morning.

I didn't catch her name, but a couple of days earlier, she had left her 2007 Toyota Camry at the curb and started taking the bus to work from upper Manhattan after the George Washington Bridge cash toll was raised to $12.

So, thanks to all. Thanks to Marta, Daisy, Jamie, Martina, Jo Anne, Liberty, Karen, Erin, Ari The Greek and all the doctors, nurses and other workers whose names I forgot.

I haven't seen the bill yet, but I also want to thank Medicare. I couldn't have done it without you.

Celebratory meals

On Tuesday night, I celebrated my release with a spicy shrimp dinner prepared at home and eaten Korean style in red-lettuce leaves with rice, kimchi, scallion and garlic.

This morning, I had my first cup of real coffee in days and later a breakfast of my wife's delicious ackee and saltfish -- Jamaican comfort food -- with boiled green banana.

That was a real welcome home.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please try to stay on topic.